by: Hayes Hunt and Calli Varner

by: Hayes Hunt and Calli Varner

On June 18, 2012, the Supreme Court came down with a fractured 5-4 decision disrupting long-standing 6th Amendment Confrontation Clause precedent as it applies to forensic evidence. Williams v. Illinois, No. 10-8505 (June 18, 2012).

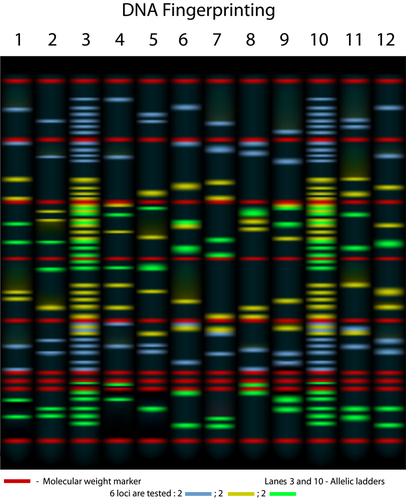

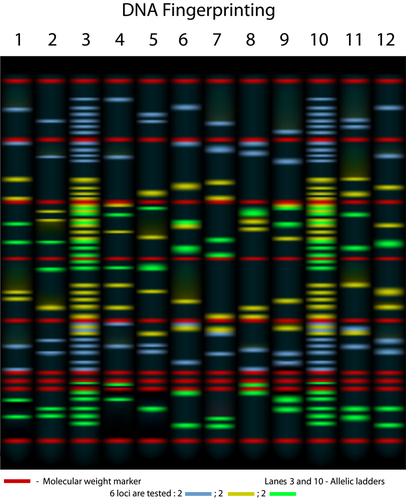

The issue before the Court arose out of a rape prosecution in Chicago. Illinois police recovered the perpetrator’s DNA sample from the victim and sent the sample to a private lab in Maryland. When the DNA profile report was returned, Illinois police ran it through their database in Illinois and found a match, Sandy Williams. During Williams’ trial, the Maryland lab report was not introduced into evidence and the Maryland laboratory technicians did not testify. Prosecutors, however, presented an expert from the Illinois state lab, who testified that it was her opinion that a DNA profile generated from Williams’ sample matched the DNA profile developed by the Maryland lab. Williams was convicted.

Later, Williams claimed that the prosecution’s failure to offer the Maryland laboratory technician for him to cross-examine was a violation of his right to confrontation. The Illinois Supreme Court disagreed and upheld his conviction.

The Sixth Amendment Confrontation Clause guarantees the accused the right “to be confronted with the witnesses against him.” In 2004, the Supreme Court held in Crawford v. Washington, that the Clause prohibits prosecutors from introducing out-of-court testimonial statements without putting the declarant on the stand. 541 U.S. 36 (2004). In 2009, in Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts, the Court re-affirmed that decision, holding that forensic reports that certify incriminating results are testimonial. 557 U.S. 305 (2009). Most recently, in Bullcoming v. New Mexico, the Court made clear that when the prosecution introduces forensic reports, it must call the actual author of the report to the stand, rather than a supervisor or other surrogate witness. 564 U.S. __ (2011).

The Sixth Amendment Confrontation Clause guarantees the accused the right “to be confronted with the witnesses against him.” In 2004, the Supreme Court held in Crawford v. Washington, that the Clause prohibits prosecutors from introducing out-of-court testimonial statements without putting the declarant on the stand. 541 U.S. 36 (2004). In 2009, in Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts, the Court re-affirmed that decision, holding that forensic reports that certify incriminating results are testimonial. 557 U.S. 305 (2009). Most recently, in Bullcoming v. New Mexico, the Court made clear that when the prosecution introduces forensic reports, it must call the actual author of the report to the stand, rather than a supervisor or other surrogate witness. 564 U.S. __ (2011).

Bullcoming, however, left open the question whether prosecutors can introduce an analyst’s testimonial forensic report through a testifying expert witness. Williams became the perfect opportunity for the Court to determine that issue.

Justice Alito, writing the plurality opinion, ruled that Williams did not have a right to confront the DNA report’s creator because the DNA report was not testimonial. The four plurality justices reasoned that the report was not testimonial because it was the expert’s testimony, rather than the report, that was offered for the truth of the matter asserted. The report, rather, was merely a premise on which the expert’s testimony was based. Justice Kagan, along with three other dissenting justices, rejected the plurality’s finding that the report was not offered for the truth of the matter asserted. As such, the dissent argued, the report was testimonial and William’s constitutional right to confrontation was violated.

Justice Thomas, in his concurring opinion, came down the middle of the road. Thomas agreed with the plurality that the report was not testimonial, but on a different basis. According to Thomas, the report was not testimonial because it was not sufficiently formal or certified. On the other hand, Thomas, agreeing with the dissent, rejected the plurality’s decision that the report was not offered for the truth of the matter asserted.

So how, in practical terms, are lower courts to interpret Williams?

As Justice Thomas made clear — formal, certified forensic reports are subject to the Confrontation Clause and the accused has a constitutional right to cross-examine the report’s creator. This means that blood alcohol, fingerprint, drug, ballistics, and related reports that are incriminating on their face will continue to be deemed testimonial and, as a result, inadmissible without permitting the accused to cross-examine their author.

According to the four-member plurality, however, reports that are subsidiary or the internal work product leading up to the formal report are not testimonial, and therefore, not subject to the Confrontation Clause. These reports are far enough removed and the accused does not automatically have the right to cross-examine their authors. If that is true, what probative value do these reports have? They are irrelevant. The plurality, it seems, put a great deal of confidence in the credibility and reliability of forensic and scientific testing.

According to the four-member plurality, however, reports that are subsidiary or the internal work product leading up to the formal report are not testimonial, and therefore, not subject to the Confrontation Clause. These reports are far enough removed and the accused does not automatically have the right to cross-examine their authors. If that is true, what probative value do these reports have? They are irrelevant. The plurality, it seems, put a great deal of confidence in the credibility and reliability of forensic and scientific testing.

As Justice Kagan pointed out, errors can potentially happen during the early stages of the creation of a report. The Confrontation Clause, Kagan wrote, is “a mechanism for catching such errors” demonstrating “the genius of an 18th-century device as applied to 21st-century evidence.”

The Court, however, did not offer this decision without warnings to prosecutors. Justice Thomas cautioned that attempts to make forensic reports less formal in order to evade the Confrontation Clause would be in vain. In his opinion, he established that the Clause “reaches the use of technically informal statements when used to evade the formalized process.” By the same token, the four-member dissent, plus Thomas, made it clear to prosecutors that they cannot evade the Confrontation Clause simply by introducing testimonial evidence through the testimony of an expert and claiming it is not offered for the truth of the matter asserted.

While Supreme Court caveats are valuable, concise evidentiary guidelines and precedents are much less confrontational.

About The Author

By Hayes Hunt and Jillian Thornton

By Hayes Hunt and Jillian Thornton , nor does the user have a reasonable expectation of privacy in information shared with third parties. “There can be no reasonable expectation of privacy in a tweet sent around the world.” Id. at *3. The court concluded that “[s]o long as the third party is in possession of the materials, the court may issue an order for the materials from the third party when the materials are relevant and evidentiary.” Id.

, nor does the user have a reasonable expectation of privacy in information shared with third parties. “There can be no reasonable expectation of privacy in a tweet sent around the world.” Id. at *3. The court concluded that “[s]o long as the third party is in possession of the materials, the court may issue an order for the materials from the third party when the materials are relevant and evidentiary.” Id.

By Hayes Hunt and Jillian R. Thornton

By Hayes Hunt and Jillian R. Thornton Given the ever-expanding universe of ESI, most lawyers would be wise to consider using computer-assisted review and especially predictive coding. After all, the research has shown that predictive coding is more precise, makes fewer errors and identifies more relevant documents than human reviewers. This should not come as a surprise when one considers the differences in opinion among lawyers about what information is “relevant.” When you add millions of pages of documents, fatigue plays a role for human reviewers. Based on these factors in addition to the dramatic saving of time and money, it is clear that predictive coding and similar methods are going to revolutionize how we conduct e-discovery.

Given the ever-expanding universe of ESI, most lawyers would be wise to consider using computer-assisted review and especially predictive coding. After all, the research has shown that predictive coding is more precise, makes fewer errors and identifies more relevant documents than human reviewers. This should not come as a surprise when one considers the differences in opinion among lawyers about what information is “relevant.” When you add millions of pages of documents, fatigue plays a role for human reviewers. Based on these factors in addition to the dramatic saving of time and money, it is clear that predictive coding and similar methods are going to revolutionize how we conduct e-discovery. By: Hayes Hunt and Jillian Thornton

By: Hayes Hunt and Jillian Thornton

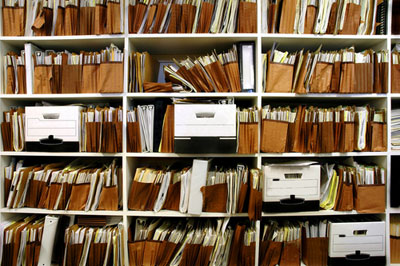

A decade ago, document review meant a small militia of lawyers sitting in a windowless warehouse surrounded by bankers’ boxes full of paper documents. Now, thanks to extreme information inflation, the bulk of document review takes place electronically. In order to keep up with the enormous volume of electronically stored information, lawyers have employed a method featuring a combination of keyword searches and manual review. Most importantly, e-discovery can be responsible for 70 to 90 percent of the client’s cost of litigation. However, recently, the universe of ESI has expanded in exponential fashion. Exabytes have devoured the smaller gigabytes in the ESI pond. What’s next? Predictive coding.

A decade ago, document review meant a small militia of lawyers sitting in a windowless warehouse surrounded by bankers’ boxes full of paper documents. Now, thanks to extreme information inflation, the bulk of document review takes place electronically. In order to keep up with the enormous volume of electronically stored information, lawyers have employed a method featuring a combination of keyword searches and manual review. Most importantly, e-discovery can be responsible for 70 to 90 percent of the client’s cost of litigation. However, recently, the universe of ESI has expanded in exponential fashion. Exabytes have devoured the smaller gigabytes in the ESI pond. What’s next? Predictive coding. costs incurred during e-discovery. Predictive coding works to drastically reduce the number of documents that are manually reviewed by lawyers. Here’s how it works: The first step in the process is that lawyers review a small sample of documents and code those documents for relevance or privilege or subject matter. The software then studies the sample set and applies the coding principles that it has learned to a larger set of documents. Then, the lawyers review the computer-coded documents to further teach the program how to code. This program continues until the software identifies only relevant documents. After coding is finished, the software can be used to select a small, random population of documents for lawyers to perform quality-control checks. If errors are found, the lawyers code more sample documents until accuracy of the coding reaches an acceptable level. Then the review is complete. The software can reduce the documents that need to be manually reviewed from a set of 2 million, for example, to only 3,000 to 5,000 documents. Assume it takes a lawyer 60 seconds to review a one-page document and you can easily do the cost-effective math of predictive coding.

costs incurred during e-discovery. Predictive coding works to drastically reduce the number of documents that are manually reviewed by lawyers. Here’s how it works: The first step in the process is that lawyers review a small sample of documents and code those documents for relevance or privilege or subject matter. The software then studies the sample set and applies the coding principles that it has learned to a larger set of documents. Then, the lawyers review the computer-coded documents to further teach the program how to code. This program continues until the software identifies only relevant documents. After coding is finished, the software can be used to select a small, random population of documents for lawyers to perform quality-control checks. If errors are found, the lawyers code more sample documents until accuracy of the coding reaches an acceptable level. Then the review is complete. The software can reduce the documents that need to be manually reviewed from a set of 2 million, for example, to only 3,000 to 5,000 documents. Assume it takes a lawyer 60 seconds to review a one-page document and you can easily do the cost-effective math of predictive coding. by: Hayes Hunt and Calli Varner

by: Hayes Hunt and Calli Varner The Sixth Amendment Confrontation Clause guarantees the accused the right “to be confronted with the witnesses against him.” In 2004, the Supreme Court held in Crawford v. Washington, that the Clause prohibits prosecutors from introducing out-of-court testimonial statements without putting the declarant on the stand. 541 U.S. 36 (2004). In 2009, in Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts, the Court re-affirmed that decision, holding that forensic reports that certify incriminating results are testimonial. 557 U.S. 305 (2009). Most recently, in Bullcoming v. New Mexico, the Court made clear that when the prosecution introduces forensic reports, it must call the actual author of the report to the stand, rather than a supervisor or other surrogate witness. 564 U.S. __ (2011).

The Sixth Amendment Confrontation Clause guarantees the accused the right “to be confronted with the witnesses against him.” In 2004, the Supreme Court held in Crawford v. Washington, that the Clause prohibits prosecutors from introducing out-of-court testimonial statements without putting the declarant on the stand. 541 U.S. 36 (2004). In 2009, in Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts, the Court re-affirmed that decision, holding that forensic reports that certify incriminating results are testimonial. 557 U.S. 305 (2009). Most recently, in Bullcoming v. New Mexico, the Court made clear that when the prosecution introduces forensic reports, it must call the actual author of the report to the stand, rather than a supervisor or other surrogate witness. 564 U.S. __ (2011). According to the four-member plurality, however, reports that are subsidiary or the internal work product leading up to the formal report are not testimonial, and therefore, not subject to the Confrontation Clause. These reports are far enough removed and the accused does not automatically have the right to cross-examine their authors. If that is true, what probative value do these reports have? They are irrelevant. The plurality, it seems, put a great deal of confidence in the credibility and reliability of forensic and scientific testing.

According to the four-member plurality, however, reports that are subsidiary or the internal work product leading up to the formal report are not testimonial, and therefore, not subject to the Confrontation Clause. These reports are far enough removed and the accused does not automatically have the right to cross-examine their authors. If that is true, what probative value do these reports have? They are irrelevant. The plurality, it seems, put a great deal of confidence in the credibility and reliability of forensic and scientific testing.

After voir dire is complete and a jury is impaneled, counsel should investigate the jury more thoroughly. As noted above, the jurors’ social media pages may provide a wealth of information that will give insight into how they will think about a case and deliberate the evidence. Counsel can use this information to better craft their arguments and examinations to specifically address the tendencies of individual jurors.

After voir dire is complete and a jury is impaneled, counsel should investigate the jury more thoroughly. As noted above, the jurors’ social media pages may provide a wealth of information that will give insight into how they will think about a case and deliberate the evidence. Counsel can use this information to better craft their arguments and examinations to specifically address the tendencies of individual jurors. • Twitter: The second-largest social network with more than 500 million accounts, this service allows users to share thoughts in 140 character bursts, along with links, pictures and video clips.

• Twitter: The second-largest social network with more than 500 million accounts, this service allows users to share thoughts in 140 character bursts, along with links, pictures and video clips. by: Hayes Hunt and Jonathan A. Cavalier

by: Hayes Hunt and Jonathan A. Cavalier Facebook, their communications can often reveal whether any allegedly harassing conduct was, in actuality, welcomed and reciprocated. Social media can also provide evidence useful in defending against damages resulting from claims of emotional distress, as users will often post about traumatic events that may have predated the alleged harassment.

Facebook, their communications can often reveal whether any allegedly harassing conduct was, in actuality, welcomed and reciprocated. Social media can also provide evidence useful in defending against damages resulting from claims of emotional distress, as users will often post about traumatic events that may have predated the alleged harassment. whether the party has discussed other jobs that might have a bearing on damages. Ask if the party has connected with any other people involved in the case. Probing a litigant’s social media profile in depositions will often provide the answers necessary to access private postings.

whether the party has discussed other jobs that might have a bearing on damages. Ask if the party has connected with any other people involved in the case. Probing a litigant’s social media profile in depositions will often provide the answers necessary to access private postings. by Hayes Hunt and Brian Kint

by Hayes Hunt and Brian Kint

by: Hayes Hunt and Jonathan R. Cavalier

by: Hayes Hunt and Jonathan R. Cavalier that would make it illegal to force an employee to allow his or her employer to view his or her private social media pages. Last Wednesday, legislation was introduced in both houses of Congress that would make it illegal for employers to force employees to give up passwords to a wide variety of social media sites.

that would make it illegal to force an employee to allow his or her employer to view his or her private social media pages. Last Wednesday, legislation was introduced in both houses of Congress that would make it illegal for employers to force employees to give up passwords to a wide variety of social media sites. by: Hayes Hunt and Brian Kint

by: Hayes Hunt and Brian Kint

Of course, the prosecution could have dealt with Pettitte’s misgivings and addressed them on direct examination. A simple question about Pettitte’s current memory prefaced with a statement such as, “I understand you are trying to remember a conversation that occurred 12 or 13 years ago, but . . .” would have reduced the adverse impact of cross examination while building the prosecution’s credibility with the jury.

Of course, the prosecution could have dealt with Pettitte’s misgivings and addressed them on direct examination. A simple question about Pettitte’s current memory prefaced with a statement such as, “I understand you are trying to remember a conversation that occurred 12 or 13 years ago, but . . .” would have reduced the adverse impact of cross examination while building the prosecution’s credibility with the jury.