By Hayes Hunt and Joshua Ruby

In a world where the overwhelming majority of cases never make it to trial, depositions take on outsized importance. They will almost certainly be the only in-person testimony either party has the opportunity to elicit and the only opportunity for live cross-examination. That means every deposition requires careful preparation.

In a world where the overwhelming majority of cases never make it to trial, depositions take on outsized importance. They will almost certainly be the only in-person testimony either party has the opportunity to elicit and the only opportunity for live cross-examination. That means every deposition requires careful preparation.

Corporations and other entities have unique obligations regarding the depositions of corporate designees pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 30(b)(6) and its state cognate, Pennsylvania Rule of Civil Procedure 4007.1(e). An entity must prepare a designated witness to answer its adversary’s questions, and the designee’s answers bind the entity in the litigation. Avoiding costly mistakes and discovery sanctions requires that both in-house and outside counsel for such entities take care to prepare for such depositions and understand the rules that govern them.

Adversary’s Responsibilities In Noticing Deposition

The entity’s adversary has few obligations in noticing the deposition of a corporate designee. All Rule 30(b)(6) requires is a notice directed to the entity that “describe[s] with reasonable particularity the matters for examination.”

Rule 30(b)(6) requires is a notice directed to the entity that “describe[s] with reasonable particularity the matters for examination.”

Notwithstanding this minimal obligation, some limits do exist on the adversary’s description of the matters for examination. The qualifier “including, but not limited to,” or other language indicating that the topics listed in the notice are not exclusive renders the notice overbroad and subject to a motion to quash. (See, e.g., Reed v. Bennett, 193 F.R.D. 689, 692 (D. Kan. 2000).)

Instead, the adversary has an obligation to define the “outer limits” of the subject matter of the deposition of the corporate designee. This limit exists to ensure that the entity is capable of designating a witness (or witnesses) who can testify about each of the topics listed, rather than facing the “impossible task” of designating a witness who can testify about all possible questions the adversary might ask.

Responsibilities Upon Receiving Rule 30(b)(6) Notice

Upon receiving a Rule 30(b)(6) notice, a corporation must produce a witness (or witnesses) for deposition questioning by the adversary. The witness(es) must be capable of giving “complete, knowledgeable and binding answers on behalf of the corporation” about each of the topics listed in the deposition notice, according to Marker v. Union Fidelity Life Insurance, 125 F.R.D. 121, 126 (M.D.N.C. 1989).

Upon receiving a Rule 30(b)(6) notice, a corporation must produce a witness (or witnesses) for deposition questioning by the adversary. The witness(es) must be capable of giving “complete, knowledgeable and binding answers on behalf of the corporation” about each of the topics listed in the deposition notice, according to Marker v. Union Fidelity Life Insurance, 125 F.R.D. 121, 126 (M.D.N.C. 1989).

Accordingly, the corporation also incurs a duty to educate and prepare its designees to testify about any matter outside the designee’s personal knowledge, which the Rule 30(b)(6) notice specifies. Failure to do so “is tantamount to a failure to appear, and warrants the imposition of sanctions,” as in United Technologies Motor Systems v. Borg-Warner Automotive, Civil Action No. 97-71706, 1998 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 21837, at *4 (E.D. Mich. Sept. 4, 1998).

Who Can The Corporation Designate?

An entity is not limited to its own present employees as its corporate designees. Instead, Rule 30(b)(6) permits an entity to designate “officers, directors, or managing agents, or … other persons who consent to testify on its behalf.”

In particular, where the relevant events have long since passed, a former employee may be the most appropriate corporate designee. In Beauperthuy v. 24 Hour Fitness USA, Case No. 06-715 SC, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 104906, at *17 n.5 (N.D. Cal. Nov. 9, 2009), for example, the court held that “the text of Rule 30(b)(6) leaves no doubt that a former employee can and should be designated as a Rule 30(b)(6) deponent, if the former employee is the most knowledgeable individual and as long as the former employee consents.”

Nor does Rule 30(b)(6) limit proper designees to people employed by or otherwise affiliated with the entity. Any “other person who consent[s]” to testify on behalf of the entity and has the requisite knowledge and preparation may do so.

with the entity. Any “other person who consent[s]” to testify on behalf of the entity and has the requisite knowledge and preparation may do so.

What Questions Must The Corporate Designee Answer?

As with any other deposition witness, the corporate designee must testify about facts within his or her (or, in this case, the entity’s) knowledge. But a corporate designee’s responsibilities go further; he or she must also answer questions about the entity’s “subjective beliefs,” “interpretation of documents and events,” and “position” on any of the topics in the deposition notice, as in United States v. Taylor, 166 F.R.D. at 361.

Some courts also permit the adversary to ask questions beyond the scope of the topics in the deposition notice. Even where the court so permits, the answers of the designee are treated like those of any other fact witness and do not bind the entity, according to Detoy v. City & County of San Francisco, 196 F.R.D. 362, 367 (N.D. Cal. 2000).

Other courts, such as in Paparelli v. Prudential Insurance Co. of America, 108 F.R.D. 727, 728-31 (D. Mass. 1985), have held that the adversary may not ask questions beyond the topics listed in the Rule 30(b)(6) notice. But counsel for the entity cannot enforce that limitation by instructing the designee not to answer the questions. Instead, the designee must answer the questions to the extent possible, and the adversary has no recourse if the witness disclaims knowledge of matters outside the scope of the deposition notice.

What Is Effect Of Corporate Designee’s Testimony?

Within the scope of the deposition notice, the designee’s answers are the corporation’s answers. That is not to say that the corporation may not later alter its answers or positions, but doing so will subject its representatives to cross-examination at trial. And the deposition testimony itself of the designee may be admissible at trial as a prior inconsistent statement, a statement against interest, or on another basis.

Within the scope of the deposition notice, the designee’s answers are the corporation’s answers. That is not to say that the corporation may not later alter its answers or positions, but doing so will subject its representatives to cross-examination at trial. And the deposition testimony itself of the designee may be admissible at trial as a prior inconsistent statement, a statement against interest, or on another basis.

The same rule applies “if a party states it has no knowledge or position as to a set of alleged facts or area of inquiry at a Rule 30(b)(6) deposition.” In that circumstance, “it cannot argue for a contrary position at trial without introducing evidence explaining the reasons for the change.”

The deposition of a corporate designee presents both risks and opportunities for a corporation or other entity involved in litigation. By understanding the rules that govern such depositions, both in-house and outside counsel for entities can use them to great effect while minimizing the risks to their client’s litigation positions.

Originally published in The Legal Intelligencer on July 16, 2014.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court recently issued two decisions regarding the use of social science experts in criminal cases. As noted by University of Pittsburgh law professor David Harris, however, the opinions appear to “come from

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court recently issued two decisions regarding the use of social science experts in criminal cases. As noted by University of Pittsburgh law professor David Harris, however, the opinions appear to “come from  se impermissible in Pennsylvania. In doing so, the Court followed the “unmistakable trend” in recent cases across the country and joined 44 other states and the District of Columbia in permitting expert testimony on this issue. Specifically, the Court was convinced that “advances in scientific study have strongly suggested” that eyewitness identifications may be inaccurate, particularly when the crime involves a weapon and the perpetrator is of a different race. In the Court’s view, effective cross-examination and closing arguments may be insufficient to inform the jury of these risks.

se impermissible in Pennsylvania. In doing so, the Court followed the “unmistakable trend” in recent cases across the country and joined 44 other states and the District of Columbia in permitting expert testimony on this issue. Specifically, the Court was convinced that “advances in scientific study have strongly suggested” that eyewitness identifications may be inaccurate, particularly when the crime involves a weapon and the perpetrator is of a different race. In the Court’s view, effective cross-examination and closing arguments may be insufficient to inform the jury of these risks.

the proposed expert testimony invaded the jury’s exclusive role as the arbiter of credibility. A divided panel of the Superior Court affirmed. In an opinion authored by Justice McCaffrey, the Supreme Court reversed, holding that “[g]eneral expert testimony that certain interrogation techniques have the potential to induce false confessions improperly invites the jury to determine that those particular interrogation techniques were used to elicit the confession in question, and hence to conclude that it should not be considered reliable.” Such issues, rather, are “best left to the jury’s common sense and life experience[.]”

the proposed expert testimony invaded the jury’s exclusive role as the arbiter of credibility. A divided panel of the Superior Court affirmed. In an opinion authored by Justice McCaffrey, the Supreme Court reversed, holding that “[g]eneral expert testimony that certain interrogation techniques have the potential to induce false confessions improperly invites the jury to determine that those particular interrogation techniques were used to elicit the confession in question, and hence to conclude that it should not be considered reliable.” Such issues, rather, are “best left to the jury’s common sense and life experience[.]” to endorse the validity of the body of psychological research behind false confessions, it has given defendants license to use similar research to challenge eyewitness identifications. One possible reason for the different outcomes is that police interrogations and confessions are familiar territories for the Court, while psychological findings regarding “weapons focus” and “cross-racial identification” are outside the Court’s experience. Indeed, the admissibility and reliability of confessions are already the subject of Miranda and other constitutional protections that have long been a staple of criminal procedure.

to endorse the validity of the body of psychological research behind false confessions, it has given defendants license to use similar research to challenge eyewitness identifications. One possible reason for the different outcomes is that police interrogations and confessions are familiar territories for the Court, while psychological findings regarding “weapons focus” and “cross-racial identification” are outside the Court’s experience. Indeed, the admissibility and reliability of confessions are already the subject of Miranda and other constitutional protections that have long been a staple of criminal procedure.  disciplines self-denominated as scientific are as objectively reliable as others.” While costs should not alone justify excluding important exculpatory evidence in criminal cases, practical concerns regarding whether expert testimony bolstering or undermining the testimony of eyewitnesses to a crime clearly warrants further scrutiny on a case-by-case basis, ensuring that the requisite elements of Pennsylvania Rule of Evidence 702 and the Frye test have been satisfied.

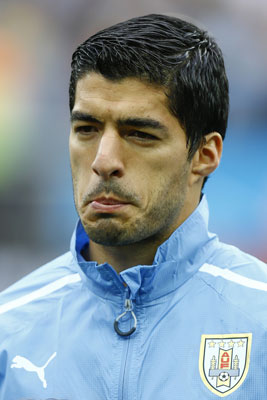

disciplines self-denominated as scientific are as objectively reliable as others.” While costs should not alone justify excluding important exculpatory evidence in criminal cases, practical concerns regarding whether expert testimony bolstering or undermining the testimony of eyewitnesses to a crime clearly warrants further scrutiny on a case-by-case basis, ensuring that the requisite elements of Pennsylvania Rule of Evidence 702 and the Frye test have been satisfied. Yesterday, Uruguay striker

Yesterday, Uruguay striker  Italian defender

Italian defender

Here, Suarez’s actions, if taking place off the field, would be deemed criminal. You cannot walk down the street and bite someone without criminal punishment. Suarez, however, has never been charged criminally; he was merely suspended for a number of games, despite the fact that this is not his first offense. This incident, of course, brings up memories of the

Here, Suarez’s actions, if taking place off the field, would be deemed criminal. You cannot walk down the street and bite someone without criminal punishment. Suarez, however, has never been charged criminally; he was merely suspended for a number of games, despite the fact that this is not his first offense. This incident, of course, brings up memories of the

On June 2, 2014, a fight broke out in the hallway of a Brevard Country, Florida courtroom. The fight was between an assistant public defender and the presiding Judge, Retired Army Reserve Colonel, John Murphy, who threatened the attorney after he refused to waive his client’s speedy trial right. Specifically, after stating that he would “throw a rock at him” if he had one, Judge Murphy demanded to see the attorney “out back” so that he “could beat [his] ass.” The video of the incident, which can be seen in

On June 2, 2014, a fight broke out in the hallway of a Brevard Country, Florida courtroom. The fight was between an assistant public defender and the presiding Judge, Retired Army Reserve Colonel, John Murphy, who threatened the attorney after he refused to waive his client’s speedy trial right. Specifically, after stating that he would “throw a rock at him” if he had one, Judge Murphy demanded to see the attorney “out back” so that he “could beat [his] ass.” The video of the incident, which can be seen in

What, if anything, should the Orlando prosecutor do?

What, if anything, should the Orlando prosecutor do? Are communications between attorneys and their retained experts discoverable? For now, the answer appears to be no, as a divided Pennsylvania Supreme Court recently affirmed a Superior Court decision “creat[ing] a bright-line rule denying discovery of communications between attorneys and expert witnesses.” Barrick v. Holy Spirit Hosp. of the Sisters of Christian Charity, No. 76 MAP 2012, 2014 Pa. LEXIS 1111, at *2 (April 29, 2014).

Are communications between attorneys and their retained experts discoverable? For now, the answer appears to be no, as a divided Pennsylvania Supreme Court recently affirmed a Superior Court decision “creat[ing] a bright-line rule denying discovery of communications between attorneys and expert witnesses.” Barrick v. Holy Spirit Hosp. of the Sisters of Christian Charity, No. 76 MAP 2012, 2014 Pa. LEXIS 1111, at *2 (April 29, 2014).  Opinion in Support of Affirmance (“the Affirmance”)

Opinion in Support of Affirmance (“the Affirmance”)

Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas Senior Judge R. Stanton Wettick Jr.’s recent ruling in Red Vision Systems v. National Real Estate Information Services, No. 14-0411 (Comm. Pls. Feb. 26, 2014), that the attorney-client privilege does not apply to corporations no longer in business has garnered significant attention, including an appeal and the filing of amicus briefing by the Association of Corporate Counsel. The ACC, which represents more than 33,000 in-house lawyers from more than 10,000 organizations, warns that allowing Wettick’s ruling to stand “would substantially inhibit the full and frank exchange of relevant information necessary for corporations to receive effective sound legal assistance.” However, Wettick’s opinion is hardly an outlier and corporate communications with counsel are subject to disclosure in many circumstances inapplicable to an individual’s relationship with his or her attorney.

Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas Senior Judge R. Stanton Wettick Jr.’s recent ruling in Red Vision Systems v. National Real Estate Information Services, No. 14-0411 (Comm. Pls. Feb. 26, 2014), that the attorney-client privilege does not apply to corporations no longer in business has garnered significant attention, including an appeal and the filing of amicus briefing by the Association of Corporate Counsel. The ACC, which represents more than 33,000 in-house lawyers from more than 10,000 organizations, warns that allowing Wettick’s ruling to stand “would substantially inhibit the full and frank exchange of relevant information necessary for corporations to receive effective sound legal assistance.” However, Wettick’s opinion is hardly an outlier and corporate communications with counsel are subject to disclosure in many circumstances inapplicable to an individual’s relationship with his or her attorney. n subjected confidential corporate communications to disclosure in circumstances inapplicable to individuals. Nearly 30 years ago, the Supreme Court ruled in Commodity Futures Trading Commission v. Weintraub, 571 U.S. 343 (1985), that the right to assert privilege transferred from management to the trustee appointed during Chapter 7 bankruptcy proceedings. In reaching this conclusion, the court noted that the corporate attorney-client privilege is normally controlled by management and, in the context of bankruptcy, the trustee’s “duties most closely resemble those of management.” In contrast, the rights of the corporation’s previous management are “severely limited.” They consisted only of turning over the corporate assets to the trustee and providing information to the trustee and creditors.

n subjected confidential corporate communications to disclosure in circumstances inapplicable to individuals. Nearly 30 years ago, the Supreme Court ruled in Commodity Futures Trading Commission v. Weintraub, 571 U.S. 343 (1985), that the right to assert privilege transferred from management to the trustee appointed during Chapter 7 bankruptcy proceedings. In reaching this conclusion, the court noted that the corporate attorney-client privilege is normally controlled by management and, in the context of bankruptcy, the trustee’s “duties most closely resemble those of management.” In contrast, the rights of the corporation’s previous management are “severely limited.” They consisted only of turning over the corporate assets to the trustee and providing information to the trustee and creditors. Nonetheless, most courts to consider the issue have agreed with Wettick that the attorney-client privilege dies with the corporation. These courts reason that once the corporate entity ceases to exist, or no longer has any officers or directors with authority to assert or waive the privilege, the attorney-client privilege no longer applies. Non-operating corporations have no management capable of asserting the privilege, nor do they have good will or reputation to maintain. The Restatement (Third) of the Law Governing Lawyers supports this view as well, noting that when “a corporation or other organization has ceased to have a legal existence such that no person can act in its behalf, ordinarily the attorney-client privilege terminates.”

Nonetheless, most courts to consider the issue have agreed with Wettick that the attorney-client privilege dies with the corporation. These courts reason that once the corporate entity ceases to exist, or no longer has any officers or directors with authority to assert or waive the privilege, the attorney-client privilege no longer applies. Non-operating corporations have no management capable of asserting the privilege, nor do they have good will or reputation to maintain. The Restatement (Third) of the Law Governing Lawyers supports this view as well, noting that when “a corporation or other organization has ceased to have a legal existence such that no person can act in its behalf, ordinarily the attorney-client privilege terminates.”

On Sept. 9, 2010, a pipeline running through a residential neighborhood in San Bruno, Calif., ruptured, permitting natural gas to escape into the air. The gas ultimately ignited, resulting in an explosion and a fire that killed eight people and injured 58 others. The fire also ravaged the neighborhood, damaging 108 homes, 38 of which were completely destroyed.

On Sept. 9, 2010, a pipeline running through a residential neighborhood in San Bruno, Calif., ruptured, permitting natural gas to escape into the air. The gas ultimately ignited, resulting in an explosion and a fire that killed eight people and injured 58 others. The fire also ravaged the neighborhood, damaging 108 homes, 38 of which were completely destroyed. The PG&E indictment raises a difficult question: When should a corporation be criminally charged? The United States Attorneys’ Manual recognizes that prosecuting corporations “enables the government to be a force for positive change of corporate culture, and a force to prevent, discover and punish serious crimes.” According to the manual, prosecution of corporations is beneficial to the public because, for instance, “corporations are likely to take immediate remedial steps when one is indicted for criminal misconduct that is pervasive throughout a particular industry, and thus an indictment can provide a unique opportunity for deterrence on a broad scale. In addition, a corporate indictment may result in specific deterrence by changing the culture of the indicted corporation and the behavior of its employees.”

The PG&E indictment raises a difficult question: When should a corporation be criminally charged? The United States Attorneys’ Manual recognizes that prosecuting corporations “enables the government to be a force for positive change of corporate culture, and a force to prevent, discover and punish serious crimes.” According to the manual, prosecution of corporations is beneficial to the public because, for instance, “corporations are likely to take immediate remedial steps when one is indicted for criminal misconduct that is pervasive throughout a particular industry, and thus an indictment can provide a unique opportunity for deterrence on a broad scale. In addition, a corporate indictment may result in specific deterrence by changing the culture of the indicted corporation and the behavior of its employees.” avoid future tragedy and change the way an industry does business. The indictment of PG&E will no doubt get the attention of all corporations in the field and force them to closely assess the integrity of their lines, as well as their safety procedures. The problem is that when a corporation’s actions result in death, injury or serious property damage, a fine seems like a small price to pay. This practical limitation on corporate criminal liability may make the indictment of a corporation feel unsatisfying for victims of corporate crime and the general public.

avoid future tragedy and change the way an industry does business. The indictment of PG&E will no doubt get the attention of all corporations in the field and force them to closely assess the integrity of their lines, as well as their safety procedures. The problem is that when a corporation’s actions result in death, injury or serious property damage, a fine seems like a small price to pay. This practical limitation on corporate criminal liability may make the indictment of a corporation feel unsatisfying for victims of corporate crime and the general public. Can a company require that you give up your right to sue the company if you download a coupon from the company’s website? What if you “like” one of the company’s products on Facebook? Over the last month, General Mills raised these questions, and then quickly responded to consumer backlash.

Can a company require that you give up your right to sue the company if you download a coupon from the company’s website? What if you “like” one of the company’s products on Facebook? Over the last month, General Mills raised these questions, and then quickly responded to consumer backlash. weighing the enforceability of an arbitration clause, allow discovery into issues such as whether an adversary agreed to the arbitration clause. See, e.g., Porreca v. The Rose Grp., No. 13-1674 (E.D. Pa. Dec. 11, 2013). Therefore, although companies like General Mills are in a favorable position to enforce arbitration clauses, it is unlikely that a court would allow a mere post on a website, without any explicit consumer agreement, to thwart all consumer lawsuits.

weighing the enforceability of an arbitration clause, allow discovery into issues such as whether an adversary agreed to the arbitration clause. See, e.g., Porreca v. The Rose Grp., No. 13-1674 (E.D. Pa. Dec. 11, 2013). Therefore, although companies like General Mills are in a favorable position to enforce arbitration clauses, it is unlikely that a court would allow a mere post on a website, without any explicit consumer agreement, to thwart all consumer lawsuits. Previously, we talked about the legal standards applied to claims of

Previously, we talked about the legal standards applied to claims of  With these standards in mind, general counsel can take a number of steps to protect confidential communications with outside consultants from disclosure.

With these standards in mind, general counsel can take a number of steps to protect confidential communications with outside consultants from disclosure. Explicitly defining the consultant’s role is particularly important if the company becomes involved in litigation in a jurisdiction that has adopted the more restrictive application of the privilege. Under this standard, communications are only privileged if the consultant was hired to perform a function “necessary in the context of actual or anticipated litigation,” according to In re Bristol-Myers Squibb Securities Litigation, No. 00-1990 at * 4 (D.N.J. Jun. 25, 2003). Accordingly, if a consultant’s work for the company can reasonably be characterized as being related to ongoing or potential litigation, reference to that issue, or the specific litigation, should be made in the retention agreement.

Explicitly defining the consultant’s role is particularly important if the company becomes involved in litigation in a jurisdiction that has adopted the more restrictive application of the privilege. Under this standard, communications are only privileged if the consultant was hired to perform a function “necessary in the context of actual or anticipated litigation,” according to In re Bristol-Myers Squibb Securities Litigation, No. 00-1990 at * 4 (D.N.J. Jun. 25, 2003). Accordingly, if a consultant’s work for the company can reasonably be characterized as being related to ongoing or potential litigation, reference to that issue, or the specific litigation, should be made in the retention agreement. Defining the consultant’s role in writing is important even under the majority approach. Communications will only be privileged if they relate to confidential information shared with consultants because of their work with the company. Permitting a consultant to have access to confidential information that is not necessary to the work he or she is performing may result in waiver of the privilege. Thus, it is crucial that the consultant’s role is unambiguous from the beginning and that the consultant is only allowed to access information related to that role. A clear engagement agreement that defines the consultant’s role can serve as a valuable reference when deciding what information to share with the consultant as their work continues to progress.

Defining the consultant’s role in writing is important even under the majority approach. Communications will only be privileged if they relate to confidential information shared with consultants because of their work with the company. Permitting a consultant to have access to confidential information that is not necessary to the work he or she is performing may result in waiver of the privilege. Thus, it is crucial that the consultant’s role is unambiguous from the beginning and that the consultant is only allowed to access information related to that role. A clear engagement agreement that defines the consultant’s role can serve as a valuable reference when deciding what information to share with the consultant as their work continues to progress. Each of these elements should be included in the company’s written policies for retaining and communicating confidential information to outside consultants. Counsel should be involved in drafting and reviewing the retention agreement to be sure that it includes the provisions mentioned above. Employees should be made aware of the company’s policies for communicating with consultants. Those policies should be in writing and made easily available. It is impossible to anticipate whether specific communications will later become the subject of litigation or a criminal investigation. Consistently controlling the circumstances of the consultant’s relationship with the company, and maintaining good communication practices throughout the consultant’s engagement, are the only way to reliably protect the company’s attorney-client privilege.

Each of these elements should be included in the company’s written policies for retaining and communicating confidential information to outside consultants. Counsel should be involved in drafting and reviewing the retention agreement to be sure that it includes the provisions mentioned above. Employees should be made aware of the company’s policies for communicating with consultants. Those policies should be in writing and made easily available. It is impossible to anticipate whether specific communications will later become the subject of litigation or a criminal investigation. Consistently controlling the circumstances of the consultant’s relationship with the company, and maintaining good communication practices throughout the consultant’s engagement, are the only way to reliably protect the company’s attorney-client privilege.